Texas. Desert Oasis in West Texas

In a remote part of arid West Texas is a cluster of low hills that has served as a reliable source of water for hundreds of years. Filled by infrequent rains, cracks and rounded pits in the red volcanic rock held water for thirsty travelers and their livestock. Later, water from the hills was used by indigenous people to irrigate crops. Early Spanish explorers called this place the Hueco Tanks (“hueco” means “hollow” in Spanish).

The Hueco Tanks cannot be considered an oasis in the true sense since they store surface runoff rather than groundwater. First to use the site were hunter-gatherers. In the mid-12th century Jornada Mogollon people relied on the water they found there to irrigate beans, squash, and corn. Living in pit houses at the base of the hills, they carved pictures into rock walls that depicted people and animals. At the time Spanish explorers arrived, the tanks were known to small groups of nomadic Kiowa, Comanche, and Mescalero Apache. While surveying the U.S./Mexican border in 1852, U.S. Boundary Commissioner John M. Bartlett visited Hueco Tanks and later reported on the rock pictographs he observed. Shortly after, Hueco Tanks became a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail Routes. In 1898, Silverio Escontrias purchased a ranch there where he built a four-bedroom house. More recently, the low hills have been a popular recreation site and county park.

Covering an area of 348 hectares, Hueco Tanks State Park was established in 1970. Geographically speaking, the park is within the southern Basin and Range physiographic province and close to the westernmost point in Texas. The Hueco Mountains and to the west and the Franklin Mountains to the east. The park’s low hills were created 35 million years ago when magma pushed a layer of limestone upwards. The magma cooled and over millions of years erosion removed section of limestone, exposing hard igneous rock. The arid climate of West Texas means that surface water is precious. The larger area around Hueco Tanks receives less than 35 centimeters of precipitation each year with half falling in July, August, September, and October. The water-holding capacity of the Tank’s volcanic rock is bolstered by holes and cracks in the porous rock. In some places surface water held in rocky holes is shaded from the sun. The park’s diverse fauna ranges from javelina to coyotes, bobcats, badgers, racoons, salamanders, and rattlesnakes. Plants include creosote bushes, cottonwood and juniper trees, and prickly pear cactus. Generally speaking, the park’s plants and animals are more typical of those found at higher elevations.

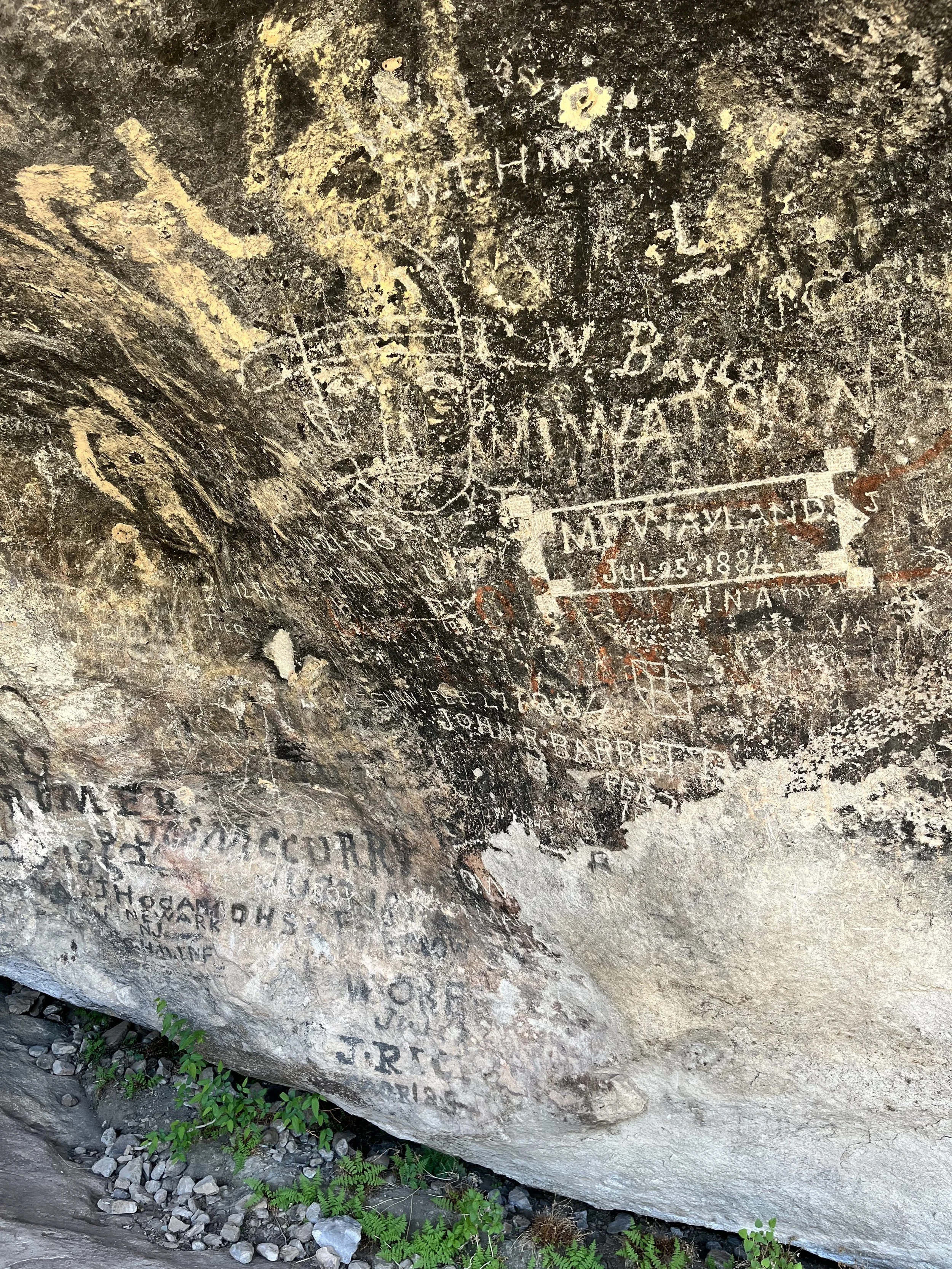

My companion and I stopped at the park’s visitor center. Hueco Tanks State Park is divided into four regions: East Spur, West Mountain, East Mountain, and North Mountain. Visitors wishing to hike are required to participate in a ranger-led orientation focused on the preservation of fragile natural and cultural resources. About two-thirds of the park is off limits to persons without a guide and tours must be booked well in advance. After completing our orientation session, we decided to hike two trails, both located on the park’s north side. The 1.0-kilometer (roundtrip) Site 17 Trail offered the chance to see petroglyphs. The park has more than 3,000 rock images including a collection found under a ledge called “Umbrella Shelter.” The most impressive single site on the trail is “Newspaper Rock” which has more than a hundred inscriptions dating from 1849 to the 1940s. Successive visitors left their names on Newspaper Rock including stagecoach passengers, Buffalo Soldiers, Texas Rangers, and homesteaders.

We followed the 1.1-kilometer (round-trip) Chain Trail which ascends rocky terrain with chain handholds for balance. The ascent to the top of North Mountain was moderately challenging and took us past several dusty pockets in the rock that hold water during wetter months. Outside of the area marked by chains, the trail has no markers so hikers can explore as they see fit.

I stopped near the summit to take photos of an ocotillo in full bloom. Ocotillos are a large shrub with long unbranched stems that rise from a small trunk. The stems have short (less than 5cm) leaves that grow during periods of sufficient rainfall and fall off to conserve water during drier periods. In wetter months Ocotillo may have red-orange flowers at the tips of each stem. Ocotillo roots and stems are used by native peoples for healing ailments or making tea.